Like many other Canadian universities, Thompson Rivers University (TRU) has great diversity amongst its student body with an increasing number of international students. According to the Canadian Bureau for International Education (CBIE) (n.d.) at the end of 2022, “Canada has seen a 43% increase of international students over the previous five years and nearly 170% increase over the last decade”. This has resulted in a 31% increase of international students in Canada from 2021 to 2022, totalling 807,750 students at all levels of study by the end of 2022 (CBIE, n.d.). Majority of international students in Canada are from India (40%) and China (12%) and most commonly reside in Ontario (51%), British Columbia (20%), and Quebec (12%) (CBIE, n.d.). The CBIE (n.d.) states the top three reasons international students choose to study in Canada is Canada’s reputation as a safe country, quality of education, and how Canadian society is generally accepting of diverse identities.

The value of education for students goes beyond content knowledge, therefore, we must analyze and break barriers such as professors’ biases towards international students’ success in order for them to reach their full potential. Due to the lack of research and empirical methodology to measure implicit bias in a post-secondary context, this paper delves into the multifaceted experiences of international students and faculty with racial bias including but not limited to linguicism, accentism and homogenization within academia. This gap likely exists due to academics being discouraged from researching their own teaching biases. Not only is there a gap in the understanding of professors’ perception of bias, but also in the corroboration of racialized international students’ experiences of bias. Through an in-depth exploration of their survey responses, this study aims to shed light on the various forms of discrimination they face, the impact of these experiences on their academic and personal lives, and the potential strategies and policies that can be implemented to create a more inclusive and equitable educational environment for all.

Current literature on teachers’ implicit biases towards racialized students mainly focuses on the experiences of students and instructors at the primary and secondary levels of education in the United States of America. Research shows a varying amount of implicit bias expressed by teachers towards students of different racial backgrounds. Gilliam et al. (2016) found that implicit biases influence teachers’ discipline disparities in primary education. In this study, an eye tracker measured participants’ gazes and recorded that Black children were looked at longer compared to White children when teachers anticipated challenging behaviors. Irizarry (2015) examined the racial differences of teachers’ evaluation of students’ literacy skills. These researchers concluded that White, Asian, and White Latino students receive more frequent above average literacy ratings in comparison to non-White Latino and Black students, indicating that students in the latter category are often regarded as less competent readers. Cate and Glock (2019) have further examined the racial differences in teachers’ perception of students’ literacy skills. They concluded on average teachers have more negative implicit attitudes toward marginalized groups’ literacy skills.

Furthermore, research has found teachers possess implicit expectancy effects of students. Peterson et al. (2016) found that students achieve more academically when their teacher’s implicit prejudice favors their ethnicity. Rubie-Davies et al. (2014) examined four types of teacher expectancy effects: “within-year effects of single teachers, cross-year effects of single teachers, mediated effects of single and multiple teachers, and compounded effects of multiple teachers”. Participants were tracked from preschool through Grade 4 on measures of achievement and teacher expectations. Teacher expectations were found to independently and significantly predict students’ year-end achievement across all grade levels, meaning expectancy effects have long-term consequences due to the correlation of achievement over time.

In addition, Boysen (2009) examined the frequency with which professors in the US perceived and responded to students’ bias in their classrooms. In this study, they found that 38% of professors noticed student bias in their classrooms in the last year and responded to it by rebutting with counterevidence to stereotypes and opening a class discussion about biases. Furthermore, Jacob-Senghor et al. (2016) have studied the impact of instructor’s teaching performance due to implicit biases. They found when White instructors taught Black students, there was a greater implicit bias associated with the professor’s anxiety that interfered with their ability to deliver clear lessons and hindered Black students’ performance.

Procedure

Ethics

All research involving human participants and/or their private records at TRU must receive approval by the Research Ethics Board (REB) prior to contacting potential participants and/or accessing private records. REB reviews are a peer review process by which the REB supports researchers by ensuring that their projects follow the The Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans (TCPS2) guide.

Participation in this study was completely voluntary and anonymous. Respondents’ names were not connected to the results or their responses on the survey; instead, a number was assigned to be used for identification purposes. Information that would make it possible to identify any participant is not included in any sort of report. This degree of anonymity was used to ensure this study would not affect the respondent’s employment, academic standing, or relationships at TRU given the sensitive nature of asking students and faculty about discrimination on campus.

Methods

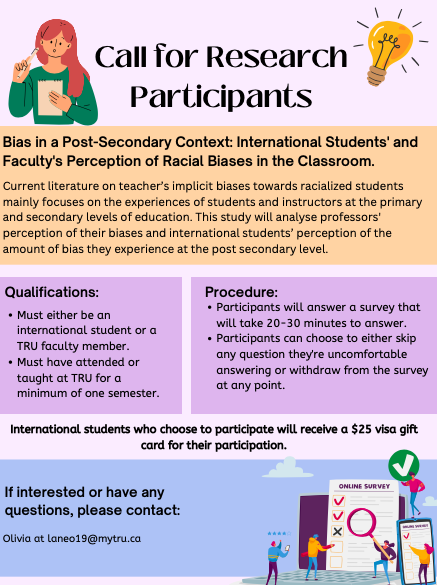

A separate survey consisting of closed and opened questions was designed for each group, international students and faculty members. The survey for international students contained 40 questions and the faculty survey contained 37 questions. Each survey contained questions concerning experiences of racial bias, mitigation practices and reporting racial biases. The total time required to complete either survey was approximately 20-30 minutes. Participants were selected based on either identifying as an international student or a faculty member that has attended TRU or taught at TRU for a minimum of one semester.

Student Survey

Promotional Posters were posted on available bulletin boards in the Arts and Education Building and Old Main. The promotional poster was also shared online by TRU social media platforms. Students who responded to the advertising were emailed the purpose of the survey, participant criteria, the promotional poster, and the link to the student survey (http://www.surveymonkey.com). After completing the survey, students then submitted an email address on a separate link attached to the last page of the survey to remain anonymous and receive a $25 gift card. A total of 26 students responded by the collection date of August 15, 2023.

Faculty Survey

An email invitation to complete an electronic form of the survey (http://www.surveymonkey.com) was sent to each faculty chair asking if they would like to participate and share the survey with their colleagues. Faculty that I have a professional relationship with and professors teaching during the summer semester according to TRU’s course registration viewing portal on MYTRU (https://mytru.tru.ca/) were also contacted via email. In every email the purpose of the survey and participant criteria was stated along with the promotional poster and the link to the faculty survey. A total of nine faculty responded by the collection date of August 15, 2023.

Analysis

Thematic analysis was used to identify common themes, topics, and patterns that repeatedly appeared throughout the collected data (Braun and Clarke 2006, 2023). In both the student and faculty responses, 24 codes were illuminated. The most common themes included language, accent, microaggressions, and generalizations. Themes such as language, microaggressions, generalizations, and faculty were deducted from the current literature. The remaining themes were inductive from the data. To ensure validity of the qualitative data, all thematic codes were reviewed by my supervisors. Additionally, demographic information was collected and analyzed to illuminate the diversity of TRU’s international student body.

Results

Student Responses

Fifteen student respondents were female and 14 were male. A majority (37.93%) of respondents reported being from India. The remaining participants were from Sri Lanka (20.68%), Nepal (13.79%), Bangladesh (13.79%), and South American countries including Peru, El Salvador, Brazil, and Ecuador (13.79%). Every respondent reported speaking two languages and 65.5 % speak at least three. Over half of the respondents (79.31%) identify as a racialized person or person of color. A majority (55.17%) of respondents have been in Canada for one to two years, 20.69% have been in Canada for only six months to a year, 17.24% have been in Canada for two to three years, and 6.9% have been in Canada for three or more years. Respondents are predominantly (58.62%) enrolled in the Bob Gaglardi School of Business and Economics, while 20.69% are enrolled in the Faculty of Arts and 20.69% are enrolled in the Faculty of Science. The median grade point average (GPA) of respondents was 3.5 and ranged from 1.86 to 4.26. At TRU, a 3.5 GPA sits on a 4.33 scale and falls right between a B+ and an A-. B-range GPAs indicate “Very Good. Clearly above average performance with knowledge of principles and facts generally complete and with no serious deficiencies” and A-range GPAs indicate “Excellent. Superior performance showing comprehensive, in-depth understanding of subject matter. Demonstrates initiative and fluency of expression” (TRU Policy Number ED 3-5, 2015). A majority (51.72%) of respondents are earning an undergraduate degree, 41.38% are earning a graduate degree, and 6.9% are earning a diploma.

Three key themes that emerged from the thematic analysis of the open-ended survey questions was language, generalizations, and group work.

Perceptions of Language Competence

A significantly high number of student respondents reported being treated differently than others based on perceptions of their English language competence or incompetence. For some, perceptions of incompetence were reflected in how they were treated and led to acts of exclusion. For others, perceptions of their competence — as compared to supposedly less competent others — were reflected in the dominant culture’s norms of English proficiency and led to them being treated with more respect. For example, one respondent expressed:

“I think I am treated better than some of the students because I have a better grasp in English language and communication but I do get subtle forms of racism and comments like “wow you have such great English for someone who comes from South Asia” and other stereotypical comments.”

Another respondent stated “I have people telling me how impressed they are with my English”. One respondent also expressed feelings of fear of being misunderstood when trying to communicate with others:

“I feel that sometimes I’m scared my peers or my professors won’t understand what I’m saying, so I hold myself back”.

Additionally, the perception of international students’ language competence can result in academic consequences. For example, one respondent stated how the perception of their language competence was used to rationalize their failing grade:

“I had a course in which nearly all the students were failing or close too. Our professor told us that he couldn’t have been more clear about the material so it must be that we don’t know enough English to understand the topics”.

Generalizations

Many respondents reported being labeled with stereotypical and inaccurate generalizations. For example, students reported being labeled inaccurately as financially affluent due to “ people [thinking] that we’re rich because we came to study abroad…”, and “that we are very well off and here just for fun”. Additionally, students also reported feelings of their cultural identity being overlooked and replaced with stereotypical generalizations of students of color. One respondent stated they have experienced:

“Comments like ” So where are you really from” or ” oh your English is great for someone who comes from a certain place” or having your opinions valued less because you are from the global south.”

Group Work

Additionally, students reported experiencing racially motivated exclusion in group work throughout their courses. Respondents stated:

“Some ethnicities did choose people of their nationality for projects” and that “it is a barrier to connect with local students because they always have their groups and it’s tough to connect with them because they are not so open apart from sitting together in class”.

Students also reported having their contributions disregarded in group work. Respondents shared how “one team did not accept my opinions in a group project “ and how “a professor was very dismissive about my contributions in class”.

Faculty Responses

Five respondents were female and four were male. A majority (88%) of respondents identified themselves as Canadian and 11.11% indicated that they were Chinese. A majority (77.77%) of respondents speak a second language, and 33.33% speak three or more languages. Only 22.22% of respondents identify as a racialized person or a person of color. Of those respondents who immigrated to Canada, collectively they had immigrated ten or more years ago. The highest level of education obtained by the majority (55.56%) of respondents was a doctoral degree, and the remaining (44.44%) have obtained a graduate degree. A majority (33.33%) of respondents are in the Faculty of Arts and the Bob Gaglardi School of Business and Economics (33.33%) while 22.22% are in the Faculty of Sciences and 11.11% are in the school of Nursing.

The three key themes that emerged from the students’ responses were also relevant to faculty responses. The thematic analysis of the open-ended survey questions among faculty members similarly reflected language, generalizations and group work. However, their responses also illuminated themes of deflection and confirmation bias.

Perceptions of Language Competence

When asked questions regarding if they assumed a student’s success in their courses is determinable by a student’s accent or language competence, many faculty stated one’s accent correlated to one’s language competence. One respondent said:

“It is not that a student speaks with an accent, but on the clarity of their English. If their speech is broken, then I assume there could be difficulty in understanding my instruction (whether verbal or written).”

This highlights how the subtle effects of linguicism and accentism, whereby the respondent takes their accent as the norm or standard (Lippi-Green, 1994), can affect international students in two different ways: either the student receives more thorough support from their faculty, or the faculty’s perception of their language incompetence is used to rationalize their lack of provided support and the student’s substandard grade. In addition, when faculty were asked if they would assume English is not a student’s first language if they had an ethnic name, a respondent said “yes, and this is usually true in my courses, but I try not to show my assumptions until I have had a chance to verify it”. Not only does this highlight how a student’s language competence is questioned before meeting their course instructors, but it also illuminates how biases can form and are sought out to be confirmed.

Generalizations

Additionally, faculty were asked questions regarding characteristics (eg. non-western names) commonly generalized of international students. For example, when asked about homogenizing international students with domestic students of color due to non-western student names, one respondent deflected the question by rationalizing their answer by stating:

“All humans categorize people based on a limited number of cues. Statistically, having an ‘ethnic name’ does indicate they are an international student the majority of the time (95%). To not assume that immediately would be strange”.

As stated by Oreopoulos (2011) The assumption of one’s skill sets due to their name has material consequences in their participation in the labour force (eg. call back rates on job interviews) due to the perception the individual may lack critical language skills. Analyzing these responses has illuminated that these assumptions may start affecting Black, Indigenous and People of Colour (BIPOC) individuals in university.

Resources and Supports

Faculty were also asked about what mitigation techniques could be employed to support international student’s lived experiences of racial discrimination and respondents agreed that Equity, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) education and resources are of utmost importance. In addition, one respondent raised an important point about how “…. Courses take too much time, but small micro-sessions are more feasible. We are all so stretched for time”. This is important to consider as time can be a possible deterrent to individuals when considering enrolling in EDI training. Another respondent stated that “proactive messaging would seem a smart thing to do” to “ensure students are aware they can ask for extra help outside of class”. Their response illuminates that while TRU has resources available for international students, they need to be communicated effectively to international students for them to be utilized.

Discussion

The Influence of Power Structures

The power structures at TRU reveal a complex web of issues related to racial discrimination and the available reporting mechanisms, resulting in the silencing of student voices due to students feeling intimidated or powerless to express their opinions. Not only did student respondents express feeling unable to either report or address their professors in regard to the bias they experience, but BIPOC faculty respondents also reported experiencing more discrimination from other faculty than students. As a result, this study has illuminated that there is a disconcerting pattern of students expressing that they sense and experience forms of discrimination in the classroom but do not report incidents of bias or racism to the institution through formal channels. Due to this, many students have become so accustomed to these issues that they perceive them as normal and sometimes even question whether it is their fault. For example, one respondent said they do not report their experiences because they “think it’s all in their head”. This normalization of bias and racism is indicative of a systemic problem, where these experiences have become ingrained in the university culture, making students hesitant to speak out or report such incidents. Consequently, this can lead to students of colour developing feelings of self-blame, self-doubt, and self-censorship to mitigate experiences of racial discrimination (Gildersleeve et al., 2011).

Furthermore, respondents indicate that TRU has an inaccessible system for reporting such incidents. Many students do not feel safe or confident in the current reporting system and some may not even be aware of its existence. As per TRU’s policy BRD 17-0: Respectful Workplace and Harassment Prevention, “members of the University community have a responsibility for ensuring that the University’s working and learning environment is free from discrimination and harassment” (TRU Policy Number BRD 17-0, 2021). However, Chairs, Directors and Deans bear the primary responsibility for maintaining a working and learning environment free from discrimination and harassment (TRU Policy Number BRD 17-0, 2021). This means they are expected to act on this responsibility and take the necessary steps to eliminate or minimize discrimination and harassment on campus (TRU Policy Number BRD 17-0, 2021). As stated in section 6.2, any member of TRU who believes that they may have experienced or witnessed discrimination is expected to report it or discuss the matter with the University’s Human Rights Officer or the Dean/Director of the department in which the concern has arisen (TRU Policy Number BRD 17-0, 2021). If a student is not comfortable reporting to either parties, they can contact a case manager within Student Affairs to make a report. All reports regardless of to whom it is submitted must be in writing and within six months of the reported event (TRU Policy Number BRD 17-0, 2021). After the report is submitted, TRU’s General Counsel will inform both parties whether the policy has been violated within four weeks (TRU Policy Number BRD 17-0, 2021). If the Counsel finds the policy has been violated, corrective action is taken “to ensure that the discrimination or harassment ceases and to prevent future occurrences of similar activity” (TRU Policy Number BRD 17-0, 2021). Such corrective measures as stated in section 11.1 “may include disciplinary action against the respondent, training for members of the university community, or amendments to university policies or processes” (TRU Policy Number BRD 17-0, 2021).

However, while this policy states corrective measures are taken to amend any harm done, previous accusations of violations of this policy such as the racism allegations of two senior administrators (racism allegations against 2 senior leaders at B.C. university) that resulted in one being terminated and their subsequent lawsuits against the complaintants, further perpetuates a lack of trust in TRU and discourages individuals from reporting. In other words, this lack of trust in the reporting mechanisms underscores the sense of the university’s failure to provide a safe and supportive environment for those who experience or witness discrimination, including its students. When students do not believe that their concerns will be adequately addressed, they are less likely to report instances of bias or racism, perpetuating a culture of silence and complicity. Consequently, as reported in the survey responses, students often resort to informal networks and conversations with friends to mitigate these issues. This reliance on peer support highlights students’ sense of the failure of the university’s official systems to address racial discrimination adequately. It suggests that the burden of dealing with these issues falls on the shoulders of the students themselves, rather than on the university administration, which should be responsible for creating a safe and inclusive learning environment.

Cultural Homogenization

Homogenization of People of Colour is the oversimplification of complex and distinct identities into a commonly western monolithic group, by disregarding the vast diversity in languages, cultures, and experiences among different ethnicities (Schuerkens, 2003). Respondents expressed experiencing the subtle effects of homogenization not only from faculty and white students, but also from other international students. For example, respondents stated they frequently hear comments insinuating People of Colour from Southwest Asia, specifically individuals from India and Bangladesh “are all the same ” and have had to explain to other students how their ethnicity differentiates from other people of color. Additionally, one respondent reported that other international students become uninterested, sometimes offended, when learning they are not of the same ethnic, linguistic, or religious background when they are of the same skin colour. Furthermore, when faculty were asked if they assume a student of colour with a non-western name is an international student, two respondents answered yes. When individuals make these assumptions, they are simplifying and generalizing a group of people based on one or more characteristics. This follows the findings of Oreopoulos (2011) who studies employer assumptions based on name alone, disadvantaging those with “ethnic sounding names” in the job search process. This homogenizing mindset fails to recognize the unique backgrounds, experiences, and identities of students who may share characteristics but have very different life stories and cultural backgrounds.

Such preconceived notions and stereotypes can have consequences in various aspects of life, including education. For example, faculty respondents have stated a strong preference for working with domestic students in regard to extracurricular academic opportunities (eg. honours projects, the Undergraduate Research Experience Award Program, apprenticeships) and emphasize their decision is based on domestic students’ higher work ethic. This preference can be attributed to inaccurate generalizations and create an environment where international students, especially those from BIPOC backgrounds, are marginalized from advancing in academia. This is referred to as racial tracking (Ware, 2021). As stated by Ware (2021) students are assessed and grouped by presumed abilities which set students up on specific educational tracks. Academic opportunities such as honours or apprenticeships are programs commonly found within an advanced track and act in a gatekeeper pattern by denying access to students who are deemed to be on other academic tracks (Ware, 2021). Not only are students on the advanced track prioritized, taken care of, and valued, but Ware (2021) also emphasizes how such students are typically white, highlighting how the tracking system is also a racial gatekeeper. The advanced tracking system acts as a racial gatekeeper denoting which students the school system thinks are important and worthy, which then determines which students receive the most educational support leading to future academic opportunities like graduate school (Ware, 2021).

Intersectional Forms of Precarity

It is apparent through data analysis that international students experience many intersectional forms of precarity. Like many other university students, international students experience multiple stressors, however, international students experience a higher amount of financial stress due to student fees, employment restrictions, and unsustainable housing.

As quoted by TRU Student Union (TRUSU) (n.d.), to register for fall and winter classes international students must pay a $5000.00 CAD non-refundable tuition deposit for undergraduate, post-baccalaureate, and graduate programs. For summer programs, international students are required to pay a full tuition deposit to register for classes (TRUSU Response, n.d.). Domestic students are only required to pay a deposit of $300.00 CAD to register for classes (TRUSU Response, n.d.). When looking at other Canadian post secondary institutions such as the University of British Columbia, Simon Fraser University, the University of Victoria, and the University of Toronto, international student tuition deposits are $1000.00 CAD or less (TRUSU Response, n.d.). Additionally, international students are required to pay on average $18,355.00 CAD in tuition per academic year, while domestic students on average are required to pay $4,487.00 CAD per academic year (TRUSU Response, n.d.). However, despite the astronomical difference in required fees, in 2022, TRU World proposed a three year “strategy for a twenty percent (20%) increase to undergraduate student and twenty-five percent (25%) increase to graduate student international tuition fees” to the TRU Board of Governors.

In addition to the very high tuition fees and unaffordable housing both on and off campus, international students are also met with employment restrictions. During an academic school year international students are usually only allowed to work 20 hours per week (Work off campus as an international student, 2023). These 20 hours can be met via more than one occupation. However, international students are not allowed to work until their academic program starts. Not only are these restricted hours limiting the amount of income they can acquire to help with tuition and housing costs, but these restrictions further restrict and stress international students by limiting them to working only during the academic year. As a result, one respondent stated this amount of stress “has led to multiple breakdowns”.

On top of tuition fees, there is a lack of affordable housing both on campus and off in Kamloops. On campus, the most expensive housing is at TRU’s Dalgliesh building, starting at $9,710.00 CAD for a studio bedroom and the North Tower building starting at $8670.00 CAD for bedroom in a two bedroom unit for an academic year (September-April). The cheapest housing available on campus is at TRU’s Dalgleish building, starting at $4180.00 CAD for a two bed studio room for an academic year. Full housing payments are expected to be paid by June 15th prior to the academic year for all buildings except for the Dalgleish building, which is expected to be paid by November 1st. If the full deposit is not paid by each date, the student is charged an additional $200.00 CAD. Students frequently have to pay this additional deposit due to federal and provincial student loans not being dispersed until late August/early September.

Due to the high cost of living on campus, international students often seek housing elsewhere in town. However, as highlighted by one respondent, international students end up “living in unsustainable housing situations, which has been happening every semester for several years, to the point where students [are] living in $1400 hotel rooms with no kitchen or [with] 7 people in a single basement suite”. Such housing arrangements leave international students vulnerable and they often do not receive empathy or support from their faculty or TRU when they are having a crisis due to not having consistent, reliable housing. Collectively, these intersectional forms of percarity are often obscured by inaccurate generalizations and stereotypes of international students as privileged travelers.

Discrimination Towards Other Minorities

This study also illuminated the discrimination of another minority group at TRU, Indigenous students. TRU has one of the largest Indigenous student population among BC post-secondary (Indigenous TRU, n.d.). One faculty respondent highlighted how Indigenous students are subjected to anti-Indigenous racist comments in and outside of class, especially when Indigenous topics such as colonialism are of subject. Additionally, the respondent highlights how WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich and Democratic) faculty frequently rely upon Indigenous students to corroborate their teaching resulting in the emotional labor of their Indigenous students. Indigenous students may feel burdened by having to repeatedly share their personal experiences and perspectives on colonialism in class. This can be emotionally taxing and can contribute to feelings of isolation and other negative emotions. Furthermore, this practice can lead to the tokenization of Indigenous students, where their input is sought merely to fulfill a diversity requirement or make the faculty member’s teaching seem more inclusive, without genuine respect for their lived experiences of colonialism. Due to this, the respondent raises an important point about how there is not just one minority that faces discrimination on campus, there are multiple minorities across campus that are affected, both international and domestic.

Limitations

This study is of course not without its limitations. Data was collected from a sample of convenience during the spring and summer semester at TRU, a semester known to have fewer students and faculty on campus. Additionally, there was no minimum response required for students to receive a gift card. This led to many student respondents either skipping over or only responding “yes” or “no” to open ended questions and some repeating responses such as “professors are racists” without providing further context. This led to a clear distinction between student respondent’s response quality and amount of time taken to complete the survey.

Recommendations

Based on the issues identified by both faculty and students, here are several recommendations to address the challenges at TRU and improve the university’s overall environment for international students:

1. Revise Tuition Fees

To address the significant discrepancy between international and domestic tuition fees (4.5x more than domestic students), TRU should consider revising its fee structure. Excessive fees can deter prospective students and a more equitable fee structure will attract a diverse range of students, promoting inclusivity.

2. Housing Crisis Mitigation

In addition to lowering tuition fees, TRU should invest in creating more affordable on-campus housing options. On campus housing needs to become more affordable and available. Ensuring affordable, safe, and accessible housing is essential for students’ well-being and academic success.

3. Incorporate EDI Content into Courses

TRU should encourage department Chairs to proactively review and incorporate EDI principles in their department’s course content. This can involve diversifying class examples and incorporating BIPOC authors’ and filmmakers into class resources. All TRU departments should be guided by an inclusive curriculum that reflects the diversity of their student body.

4. Enhance the Current Reporting System

TRU needs to establish a more effective reporting system for incidents of bias and racism on campus. This system should be easily accessible and student-driven, allowing them to voice their concerns. TRU should conduct surveys and consult with students to determine their preferences and requirements for a reporting system that they trust and feel safe using.

5. Multilingual Resources

University resources should be accessible in multiple languages to accommodate the diverse student body. TRU already offers free multilingual counseling through the Keepme.SAFE app, however, providing information about other services in various languages can ensure all students are able to locate and access other needed resources.

6. Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion Training

EDI training should be available for both staff and students at minimum once per semester. TRU can either utilize existing resources such as previous EDI instructors, or explore online options and collaborate with BIPOC community organizations to develop comprehensive training programs. These programs should emphasize cultural sensitivity, inclusivity, and awareness of the challenges faced by underrepresented groups.